In paid partnership with Tracksuit. Data provided by Tracksuit; editorial control by THE GOODS.

MELBOURNE—It’s 5:30am when Abigail Forsyth, Co-founder of KeepCup, joins our video call. Neither of us had accounted for the seasonal time shift; by the time we realised the hour would land squarely in pre-dawn territory for her, it was too late to reschedule. She appears unperturbed.

As we begin tracing KeepCup’s beginnings, it is clear that the mission that launched the brand is still Forsyth’s anchor behind why it exists at all today.

Forsyth grew up on the outskirts of Melbourne, in a house her parents built among horse paddocks. It was there, lying in the grass and watching insects move through their tiny universes, that she first sensed the outdoors had a kind of order worth respecting. “I remember feeling a great sense of peace lying on the grass and watching the insects… I’ve always connected a sense of vitality to the natural world.”

She pauses, allowing a brief, reflective smile to surface. “I had a geography teacher at school who I really loved, and she really helped foster that regard for the natural world in me.”

During a school excursion to the sand dunes, the teacher, usually placid, sharply interrupted the class’s carefree rolling down the dunes. You’re causing erosion. You’re destroying the wildlife. “I hadn’t thought of that before,” Forsyth says.

That early understanding of cause and effect likely guided her initial move into law and, subsequently, into entrepreneurship.

By the late 1990s, as Melbourne’s coffee culture accelerated and the flat white gained international traction, the cafés she ran with her brother Jamie, Bluebag, were at capacity from opening through close. Each week, thousands of coffees were served. Yet a clear operational contradiction persisted: waste bins remained consistently full of single-use cups. The waste was not just an environmental blight. It was evidence of a system that treated disposables as an unavoidable cost of doing business.

In 2019, Harvard Business Review published an article entitled The Elusive Green Consumer. Their research suggests that a primary driver of disposable coffee cup consumption, “a habit repeated a staggering 500 billion times annually worldwide”, is the response to environmental cues. These include defaults such as the cup automatically provided by the barista and visual prompts like trash bins marked with images of cups, both of which are ubiquitous in coffee shop settings.

Even today, Starbucks alone distributes approximately six billion disposable cups a year, with a target to eliminate them by 2030; more than two decades after the founding of KeepCup.

Recent data suggests the problem remains unresolved. Brand-tracking firm, Tracksuit finds that 64 percent of US adults now fall within the reusable bottles and cups category. It is a market shaped less by novelty than by habit and personal values, environmental consciousness, practicality, and durability. Everyday drivers within which KeepCup has long operated.

Demographically, the category skews 25–34 years, a segment highly aligned with sustainability-minded and design-led brands—both core strengths for KeepCup.

When the thermoses available at the time proved too bulky to fit beneath the espresso machines at Bluebag, Forsyth and her brother identified a gap: a reusable cup designed to integrate seamlessly into the barista workflow while reducing waste and operating costs for the business.

In this edition of Blueprints, we examine Abigail Forsyth’s founder journey from category creator to category survivor, and how innovation, creative discipline and clear leadership enabled KeepCup to remain resilient as the market matured and competition intensified.

In the conversation that follows, Forsyth traces the decisions that turned KeepCup from an idea into a durable business.

For us, it just seemed so obvious. We thought there’s something we’re missing here. Why are these products growing and so ubiquitous when they can’t be recycled? Why are we even making these things? Have we missed something?

The risk was that there was something we had missed in the fact that disposable cups existed in the first place, or that there was something missing in our solution. When we first took them to market, we had to spend a lot of time convincing cafés that there were no health regulations preventing them from refilling reusables, to the extent that we got a letter from the council in Melbourne and the Premier saying there was no health risk.

My background is law. I was a lawyer. All that didn’t intimidate me. It galvanised me because there was a gap in the common sense of it all. It was just something people had assumed without really thinking through whether it was actually true.

I found that quite exciting in the end, that you were asking people to bridge a gap between: does this make sense? No, it doesn’t. Well, let’s do it this other way. That was the fun bit.

I wanted it to be as sustainable a product as possible. We wanted to manufacture it locally. I went around to all these manufacturers and one guy said, “Are you mad? This is a plastic cup. There’s nothing about it. If you can’t sell it, then you’re wasting your time.” It was actually really good advice: if you’re not prepared to pitch it and talk about it, you won’t sell a thing.

We got an order of 5,000 from Energy Australia. They were giving it as a gift for all their employees as part of a roadshow and we were right up against the wall with the time frame. They paid us the deposit. We were there on a Saturday at the manufacturer. I remember the girl printing the bands. She was supposed to be at a wedding, so she was really annoyed, and she was printing these bands.

We packed them all up at the kitchen table and we had no time, so we flew them up to Sydney and dropped them off. I was sitting at the airport and the customer called and said, “We can’t use these. They’re leaking and the print is coming off the cup.” I was just like, oh.

I do remember thinking that this could be it.

She knew she was the first one to get this product and she said, “Look, I thought this might happen. I’ve got a backup gift and if you can get it right for the next quarter, we’ll continue with the order.” We got it right and it all worked out.

In the end, it was a good thing and it gave us more confidence in the product. If she hadn’t been kind enough to tell us, imagine it just going out and being rejected. You’re done.

Yes. We sold ten thousand before we even had a product. We’d sold five thousand to Energy Australia. We then secured an opportunity with the National Australia Bank. We said to them: you’ve just moved into a six-star-rated building, you’ve got grey water, you’ve got solar panels, but everyone is walking around drinking from disposables. You’re connecting your mission to all these things people can’t see and touch and feel, and then you’ve got this thing in your hand.

That was our pitch. They agreed with us and bought five thousand.

Then we went to a design show and we sold a thousand cups in six hours. People were saying, “I don’t want to use those disposables, I want one,” “I love the colours, the design” or, “I’ve been thinking about this.” It was something that was on people’s minds at the time.

It was a time of real optimism in people about sustainability. Sustainability went from being the greenies in the corner to being everyone. People felt galvanised that if we all chipped in, we were going to make a difference and see this thing through.

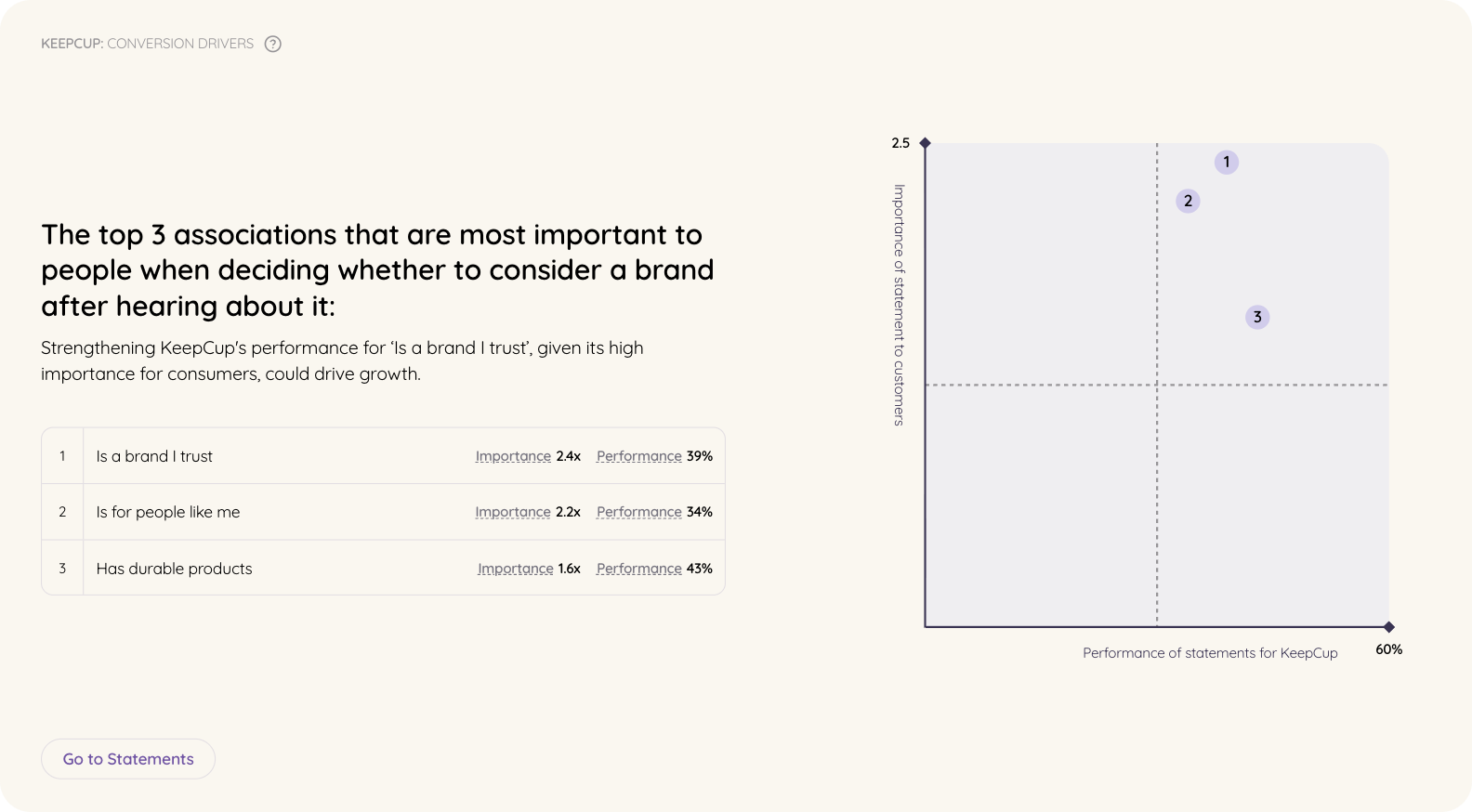

Tracksuit's conversion driver analysis shows that the three strongest factors influencing consideration in the US reusables market are trust, relatability (“a brand for people like me”), and durability. KeepCup performs strongly across all three, placing it in the top tier for brands converting interest into intent. The priorities Forsyth describes: design discipline, longevity and restraint, map directly to what still moves buyers today.

There are a lot of amazing people chipping away at problems and doing incredible things, but I think the public is a bit disengaged.

I think the pandemic was a real dis-engager for people, because you saw how quickly governments could make a change. Overnight, we were all locked in our homes. They’ve got the power to do it [ban disposables] and yet there are all these big, gnarly problems where they’re not making quick, decisive, far-reaching decisions.

I didn’t realise that the concept of the “carbon footprint” was invented by an oil company. This whole idea that you’re pushing responsibility onto the individual. Responsibility has been a corporate play forever. It’s like: it’s not us, it’s you. If only you disposed of the rubbish. If only you…

Yes. In a way, our individual behaviour-change mantra became a bit complicit with that idea of not holding the big companies to account.

Keep Australia Beautiful and all those litter-picking movements are backed by Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and the big litterers. You can see the message is, “It’s not a problem with us, it’s you. You need to pick up your rubbish.” That’s the whole corporate responsibility thing.

We still choose to move our supply chains to recycled material even though it costs a bit more. We look at light-weighting our packaging. Everything about our supply chain is uncompromised in our effort to minimise our carbon footprint in what we’re doing.

The way we sell has never changed. We’re not trying to get you to buy fifteen in every colour of the rainbow. In order to compete we are moving towards becoming a lifestyle brand in the sense that we’ve got a whole suite of reusable options, which is unavoidable, but we don’t market that you need fifteen of the same thing. It’s still that buy once, buy well idea.

We’re just meeting people where they are and how they drink. Younger people are moving to more iced beverages, so we meet them there with a product that suits the way they drink.

It’s the team. In the early days I was so excited by what was happening, I was very happy to talk about it. Because I knew the sustainability story, I guess it was my story, so that made sense. As things have progressed, I’m not so keen to be the face of the brand, but it’s effective. I love founder-led companies.

I think more and more, founders and the C-suite need to be front-facing for people to buy into a brand.

Abigail then zooms out, from her own role to the broader question of who is meant to answer for a brand’s choices.

The consequence of this tension between individual behaviour change and corporate responsibility is that what sits at the heart of both is still personal accountability, whether you’re an individual or a business. It’s the same thing, just multiplied out.

What you’re seeing in bigger companies is: who am I talking to? Am I talking to an individual? Am I talking to the business? There’s a bit of confusion about accountability at the moment. It’s probably always been the case, but right now I think we’re all a bit confused about what we’re responsible for and who we’re accountable to.

Be really clear about what your values are and why you’re there. You’re going to have to tap into that often to make hard decisions and fun decisions.

Then that evolves into looking at your team. Who are you surrounding yourself with? That includes your own business team, but also your suppliers, the agencies and other partners you engage.

What happens over the years, particularly with a smaller business, is if you get someone who’s really strong in IT, suddenly everything in the business becomes a tech solution and you start drifting down that path. Or if you get a really great sustainability communications person, then everything is talked through a sustainability lens.

As a leader, it’s important to know what you know, and to know that you don’t know what you don’t know.

You start to lean in and think, “I don’t know anything about tech, that’s really interesting,” and suddenly you’re off down a path that might not be the right one. You have to be patient with that. You’re going to make heaps of mistakes. That core “why”, why you started the brand, matters.

We’ve actually worked with the same agency from the very first day. They came up with the name KeepCup. We always turned back to them for that creative inspiration.

But I would say most of our spend in the early years was on attending trade shows in the specialty coffee space. At that time, the coffee trade shows were very coffee-machine-oriented, and we came with these bright, fun cups that were a bit of a breath of fresh air in that space.

It’s a lovely community of people who are very open and receptive. They were really important to the growth of the brand and the business.

Probably not. The world has changed a lot. We were caught on the hop. We were not a very tech-driven business and we’ve had to learn those skills in the last five years, and deal with influencers. I still struggle with it.

I understand that what’s happening in the digital world is what we did in real life, but there’s a lack of sincerity there that I find concerning.

Yes, it is, but it’s in the same position that KeepCup has been in for the last five years. It’s like the genius of the Patagonia “Don’t buy this jacket” campaign. Everyone says, “That’s so clever, that’s amazing,” but is it? Or are you just still buying another jacket? It’s still a campaign to get you to buy more.

There is something absolutely valid about knowing you’re buying from a business that treats staff well, is thinking about the downstream consequences of its actions, has a good supply chain and transparency in its governance.

But the challenge is: how does it grow and who is in the club? It became a club of people who were feeling a bit worthy.

What is the point? Is it to be an amazing group of companies that is a high bar to achieve, or is it to encourage all companies to adopt the same principles? That’s its challenge.

The more you move into that space, the more you’re in the “buy this now” cycle. We were pretty hopeless. I was always like, no one wants an email. If you want a product, you can find it. We don’t need to email people all the time.

Then my team said, I think you do need to email people. So we do now. And we do two sales a year. We don’t do that many discounts, but time will tell.

For us it’s always been about talking about the pleasure of drinking from the product, the quality of the product, the downstream effect of doing so, and then enjoying the beverage. Because we’ve got glass, because we’ve got clear products, the real hero is the drink.

In terms of legislative change, I’d be saying: see you later, we’re done here with disposables. It’s fanciful, but I think in the time that KeepCup’s been around, there is probably more single-use packaging than there has ever been.

For a lot of people, what KeepCup has done is change their behaviour so that if they don’t have a KeepCup, they just have the coffee in-house. It has changed behaviour, but it has segmented the community. The people who are doing it are committed, and once you’re fully committed to that journey, you adopt that behaviour elsewhere.

You think, “I’m not going to get a water bottle, I’ll just get it from a tap,” or “I’ll just be thirsty and wait until I get where I’m going.” People make those decisions.

Anyone who has worked in retail would know that every single item of clothing that’s made comes in a plastic bag, a single plastic bag. The volume of plastic that is hidden, that we don’t see, and then it’s all pretend out the front, is mind-boggling.

A lot of the work of sustainability is really behind the scenes. You don’t see it. Our products don’t come in a plastic bag and getting the manufacturer to do that was an extraordinary feat of negotiation, because, they argued, “this is how we do it, we put it in a plastic bag.”

We have a system where the cartons that the product comes in are the cartons it’s delivered in. We’re reusing those cartons in the back of the warehouse all the time to minimise our packaging.

It’s difficult to tell that story. First you have to say, “Hello, we’re KeepCup,” then, “We’ve got these amazing products,” then, “They’re made from recycled materials,” and by the time you get to the supply chain, people have moved on.

We had a marketer come in and say, “This is about brand. This is not just about the product and sustainability. You’re not just solving an environmental problem; you’re selling a product and a brand. Step forward with that.”

More recently, we’d always worked externally with designers. When I talk about the brand, I never used to speak about the product design, which is so core to the business. It’s what we spend half our time thinking about. We brought a designer in-house maybe two years ago. It completely changed the business. It changed the velocity of our design and kept that design really tight, really in-house and true to who the brand is. We’ve got a small team and we work on that all the time. It’s incredibly rewarding and it’s delivering results.

We do a lot of things where, for example, we saw the trend of iced coffee and made another lid that goes on a cup we already had. There’s a lot of MacGyver-type modularity and innovation happening where we’re putting a spin on something that’s good for customers. We’ve just relaunched the website, so we’re going to be able to tell that modularity story in a much clearer way now.

For me it would be returning to family, but probably mainly nature. Going for a walk in a forest or on the beach. We go down to the beach often. I often go walking. My two children love it.

I’ve got a 15-year-old boy. He loves walking. We went for an overnight hike in the summer, which nearly killed me. I said to him, “Why do you like this?” and he said, “I find it really peaceful.” And I thought, yes, I do too.

Forsyth’s founder story illustrates how a company’s operating model, product design, and stated purpose can remain aligned over time. Few brands maintain that coherence and manage to stay purpose-led as markets mature.

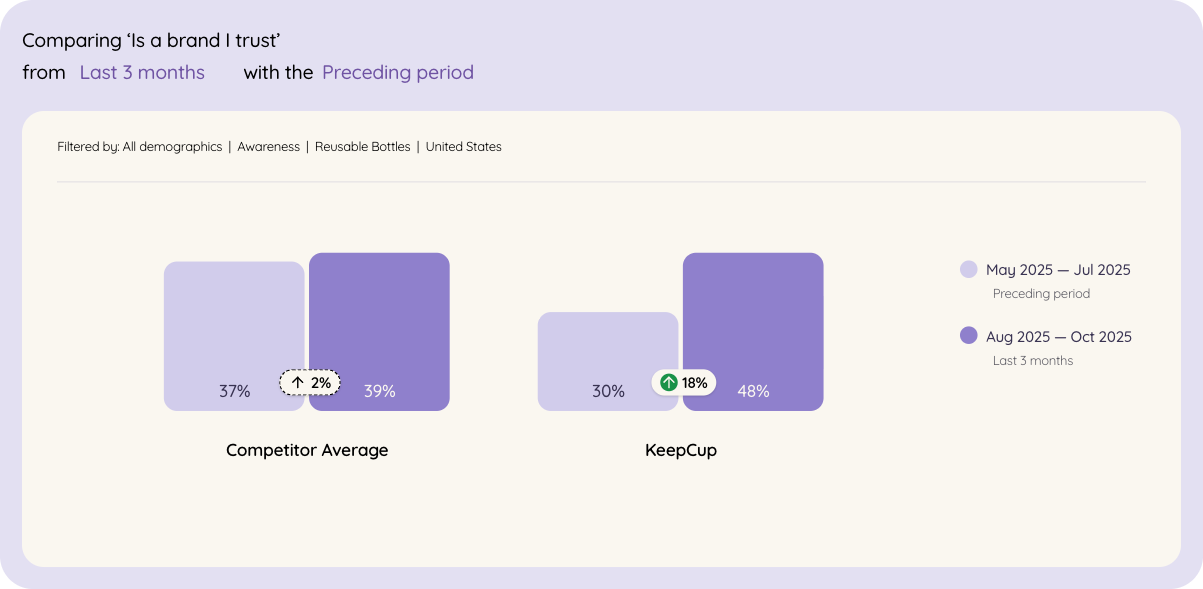

In the US over the past three months, trust in KeepCup rose from 30% to 48% (+18 points), versus a +2-point average among tracked competitors, according to Tracksuit. Over the same timeframe, “for people like me” increased from 28% to 41% (+13), again ahead of competitors.

This outcome reflects years of disciplined decision-making across manufacturing, supply chain, pricing and product design. The data points to a brand that is not only loved for its values but is rapidly building credibility and social proof — critical foundations ingredients for long-term growth.

Categories do not remain static; they mature, commoditise and frequently come to favour the largest and loudest players. What endures with KeepCup is a clear anchoring to its founding principles, supported by a consistent willingness to make the unglamorous, high-integrity decisions required to uphold them. The business did not pursue volume for volume’s sake, dilute its proposition as the category became crowded, or allow sustainability to devolve into rhetoric rather than operational practice.

Had Forsyth and the team compromised on those principles, commercial returns may have been larger, and realised sooner. Perhaps. But on what basis would that wealth have been created, through operational shortcuts or through brand drift? The more durable view is that discipline is an economic strategy. KeepCup’s trajectory suggests that foregoing the easier path has generated a more resilient and enduring form of value.

–

Since 2009 KeepCup has sold over 12 million units, potentially diverting billions of disposable cups from landfill; The brand operates globally with offices and production in Australia, the UK and US.